По Европе с середины 2000-х годов ходит большая частная коллекция русского и украинского авангарда, состоящая из сотен шедевров, — картин Лисицкого, Родченко, Экстер, Гончаровой и других мастеров.

Известная как коллекция Закса по имени владельца, она продавалась в Европе за сотни тысяч швейцарских франков.

Сейчас работы из коллекции Закса висят в двух важных американских музеях и одном европейском. Одна из них попала в недавние голливудские фильмы, в том числе “Оппенгеймер” Кристофера Нолана.

Но эксперты говорят, что картины могут быть подделками, а история происхождения коллекции — набором мифов и фантазий.

Пока трое арт-детективов расследовали эту легенду о потерянном Граале русского авангарда, Би-би-си искала ее загадочного владельца и тех, кто помогал ему продавать сомнительные картины.

Из белорусских сел на швейцарские аукционы

В начале 2000-х годов в Минске объявился никому не известный частный коллекционер, спешивший сообщить хорошую новость: нашлась огромная коллекция картин русского авангарда, и он хочет выставлять их в Беларуси.

В коллекции было больше двух сотен картин, включая полотна Лисицкого, Родченко, Татлина, Чашника, Гончаровой, Поповой, Экстер, Клюна, Фалька и других мастеров.

Ее загадочным владельцем был советский эмигрант Леонид Закс, ныне гражданин Израиля. Он рассказывал, что уникальную коллекцию собрали его родственники, получившие часть шедевров в подарок от белорусских крестьян, а остальное купившие то ли в московских, то ли в минских комиссионных магазинах в 1950-х.

Белорусские чиновники от культуры восприняли историю с энтузиазмом и организовали несколько выставок. “Это уникальные работы, от них исходит тепло, доброта, непосредственность. Мы очень благодарны Вам за то, что сберегли их для нас и для будущих поколений”, — благодарил Закса заместитель министра культуры Беларуси.

Но искусствоведов насторожило и то, что Закс старательно избегал Национальный художественный музей Беларуси, и исторические ошибки в его интервью, и наконец само качество картин.

“Эта история рассчитана на людей, которые совсем уж оторваны от нашей действительности”, — говорил витебский историк Александр Лисов в интервью Tut.by.

Лисов обратил внимание на мистификацию: в каталоге одной из белорусских выставок указывалось, что подлинность работы подтвердила “Н. Селезнева”, сотрудница Русского музея в Петербурге. Но такой сотрудницы в музее никогда не было.

После этого интервью в Беларуси выставки больше не проводились. Статья о коллекции Закса была удалена из “Википедии”.

Впрочем, это не остановило коллекционера, а лишь сменило поле его деятельности. Выставки продолжились, но уже в частной швейцарской галерее Орландо в Цюрихе.

В 2007—2014 годах прошли по крайней мере пять больших выставок коллекции Закса. Это коммерческая галерея, и все картины были доступны для продажи.

Большинство из них были куплены частными коллекционерами — иногда за сотни тысяч швейцарских франков. Для одной семьи эти покупки привели к семейной драме.

Искусство для слепых

Когда Рудольф Блюм, легендарный цюрихский коллекционер, ослеп в 2005 году, дело подхватила его жена Леонор. Она начала активно покупать русское искусство через цюрихскую галерею Орландо, доверяя своей знакомой, ее владелице Сюзанн Орландо. Леонор Блюм успела купить десятки картин на миллионы швейцарских франков.

Среди этих вещей — полотна авангардистов первого ряда: Лисицкого, Родченко, Поповой, Татлина, Экстер. Одна из работ Лисицкого была куплена за 400 тыс. швейцарских франков, другая — за 500 тыс. Картина Любови Поповой — тоже за 500 тыс..

“[Мама] хотела доказать, что разбирается в живописи не хуже отца, и верила Сюзанн Орландо” — вспоминает Беатрис Гимпель Макналли, дочь Блюмов. — Отец начал подозревать неладное, но что он мог сделать?”

К моменту, когда она начала покупать эти картины, у Леонор Блюм уже была диагностирована сосудистая деменция. Но когда Беатрис поделилась своими сомнениями с матерью, та не только отвергла их с негодованием, но и смертельно обиделась.

Эти картины навсегда испортили их отношения.

Подозрения Беатрис оправдались. После смерти ее родителей оценщики наследства сказали, что картины из коллекции Закса ничего не стоят. Аукционные дома в Лондоне отказались их рассматривать, но в одном из них ей посоветовали обратиться к Джеймсу Баттервику — британскому дилеру и знатоку русского и украинского авангарда.

“Мощь российской экономики”

До 2022 года галерея Джеймса Баттервика специализировалась на русском и украинском искусстве, но после “русское” исчезло из ее названия. Искусство в основном осталось прежним.

До недавнего времени “русским авангардом” называли работы художников, созданные в первой четверти XX века на всем пространстве от Витебска и Киева до Москвы и Петербурга, и в это понятие включались такие течения как супрематизм, конструктивизм, лучизм, кубофутуризм и т.д. Сейчас такое обобщение считается неуместным, а для кого-то — империалистическим и колониальным термином. Всё чаще используются альтернативные определения, например, “советский” и “украинский” авангард.

Увлечение советским авангардом для Баттервика началось со студенческого обмена в СССР и закончилось переездом в Москву в 1994 году. Поездка на праворульном Citroën BX заняла три дня с ночевками в Ганновере, Познани и Минске.

В это время, с приходом рыночной экономики, рынок искусства вышел из подполья, и на него хлынул поток подделок. Но тогда, в начале 1990-х, речь шла не о массовом производстве фальшивок, а скорее о некритическом отношении к старым вещам.

Все изменилось в 2000-е, когда русский капитал вышел из родных берегов. В декабре 2004 году на двух лондонских аукционах были представлены больше тысячи картин русских мастеров. Их покупали в основном русские.

Взлет цен на картины русских художников отражал “высокий спрос на них в России и мощь российской экономики”, говорили эксперты.

Вскоре авангард вышел на первый план, подвинув академическую живопись. Интерес к Шишкину и Айвазовскому уступил место погоне за полотнами Малевича и Кандинского.

“Российская буржуазия по мере повышенных темпов наращивания капитала стала претендовать на космополитизм”, — вспоминает Михаил Каменский, искусствовед и куратор, в прошлом глава Sotheby’s в России и замдиректора Пушкинского музея.

“Работа над фальшивками”

В ноябре 2008 года, в разгар мирового экономического кризиса, “Супрематическая композиция” Малевича ушла на нью-йоркском аукционе за 60 млн долларов — рекордные для русского искусства. Десять лет спустя эта же картина будет продана за 86 млн.

Взлет цен привел к появлению индустрии производства и обслуживания целых поддельных коллекций, говорят эксперты.

Вскоре в ходе полицейских рейдов в Европе начнут находить склады с сотнями и порой тысячами картин непонятного происхождения.

Баттервик вспоминает, как однажды в Москве знакомый подвозил его на своем предсказуемо огромном внедорожнике:

“Машина была забита десятками картин, которые казались мне крайне сомнительными. Я спросил его о них, и он стал показывать мне сертификаты подлинности”.

Джеймс стал замечать, что все больше и больше сомнительных картин, которые ему показывали его клиенты, сопровождались статьями и заключениями от экспертов.

Такие бумаги прилагались и к картинам, с которыми Беатрис обратилась к Джеймсу. Это были заключения искусствоведов из InCoRM. Аббревиатура расшифровывается как “Международная палата русского модернизма”. Ее создатели позиционировали себя как объединение исследователей русского авангарда.

В комплекте документов были также статьи белорусского искусствоведа Татьяны Котович и научного сотрудника Русского Музея Антона Успенского. В галерее Орландо выдали семье Блюм переводы их статей в подтверждение подлинности картин.

Джеймс решил разобраться в этой истории вместе со своими товарищами, украинским куратором Константином Акиншей и петербургским коллекционером Андреем Васильевым.

Акинша еще 1996 году написал для нью-йоркского журнала ARTnews статью “Фальшак”, в которой раскрыл десятки работ, ошибочно проданных на европейских аукционах как работы мастеров авангарда. Это было первым расследованием, показавшим масштаб проблемы на рынке. С тех пор он регулярно возвращался к этой теме — и консультировал Музей Людвига в Кельне, который признал множество своих русских и украинских работ подделками.

Васильев — автор книги “Работа над фальшивками” о портрете Елизаветы Яковлевой. Эта картина выставлялась в британской галерее Тейт, московском павильоне “Рабочий и Колхозница” на ВДНХ и ряде европейских музеев как неизвестная прежде работа Казимира Малевича — и продавалась за 22 миллиона евро. Васильев же, используя архивы, доказал, что это работа забытой ленинградской художницы Марии Джагуповой.

Исчезающий дядя Моисей и везучая тетя Анна

Изучение подлинности картин традиционно строится на трех китах: мнениях экспертов, технико-технологическом анализе и провенансе, то есть истории происхождения вещи.

Акинша — соавтор учебника Ассоциации американских музеев по изучению провенанса, и он предложил разобраться в невероятной истории коллекции.

По словам Закса, основоположником коллекции был его дед Залман, торговец и кожевенник из Екатеринослава (ныне Днепр в Украине). Залман якобы увлекся радикальным искусством, увидев его в бельгийском банке в Екатеринославе, и начал скупать картины.

Дело отца продолжила Анна (Нехама) Закс, военный медик. В 1944—1945 годах она лечила белорусских крестьян в треугольнике между городами Лепель, Чашники и Ушачи. Только что освобожденные из-под нацистской оккупации крестьяне в благодарность за ее труды несли ей картины Лисицкого и Экстер.

А окончательный вклад в будущую коллекцию внес брат Анны Моисей, пропавший в 1941 году на фронте, а в 1950-х как будто объявившийся в Москве уже как американский бизнесмен. В то время Центральный клуб культуры МВД проводил семинары, осуждавшие “формалистское искусство”, после которых работы авангардистов сдавались в комиссионные магазины.

Моисей Закс, утверждает семейное предание, скупил несколько десятков этих шедевров в 1955—1956 годах — и вывез их все в Европу. Там они лежали до 1990-х, когда коллекцию унаследовал его племянник, нефтяник из Москвы по имени Леонид Закс, который и рассказывал эти увлекательные истории про своих родственников.

В качестве доказательства Закс представлял покупателям письмо из Национального музея истории и культуры Беларуси от 2008 года, детально описывающее всю эту историю, но со значительными противоречиями, странными опечатками и ошибками. В этой версии дядя Моисей исчезает из истории, и единственным собирателем коллекции остается тетя Анна Закс. Вместо дома культуры МВД местом антиформалистских семинаров указан уже “минский горком КПСС”.

В ответ на запрос Васильева в Национальном музее истории и культуры сообщили, что “такого письма в архиве музея не обнаружено”. “Так же сообщаем, что нумерация исходящих писем за 2008 год использовалась без буквы “М””, — говорится в письме.

“То есть по всем параметрам это письмо является фальшивым”, — заключает Васильев.

Но на этом арт-детективы не остановились. Они провели исследования в российских и белорусских архивах, написав десятки запросов в музеи и проверив все ключевые факты этой истории. В МВД РФ на их запросы ответили, что в центральном клубе МВД подобных выставок никогда не проводилось; более того, он был закрыт в 1949 году и открылся вновь лишь в 1966-м. В МИД РФ ответили, что изучили свои архивы и не нашли никаких упоминаний о въезде Моисея Закса в эти годы.

“Мы проверили весь провенанс коллекции Закса, и каждый элемент этого провенанса не подтверждается ничем, скорее мы способны его опровергнуть. Перед нами классический провенансный миф”, — говорит Акинша.

В музеях и голливудских фильмах

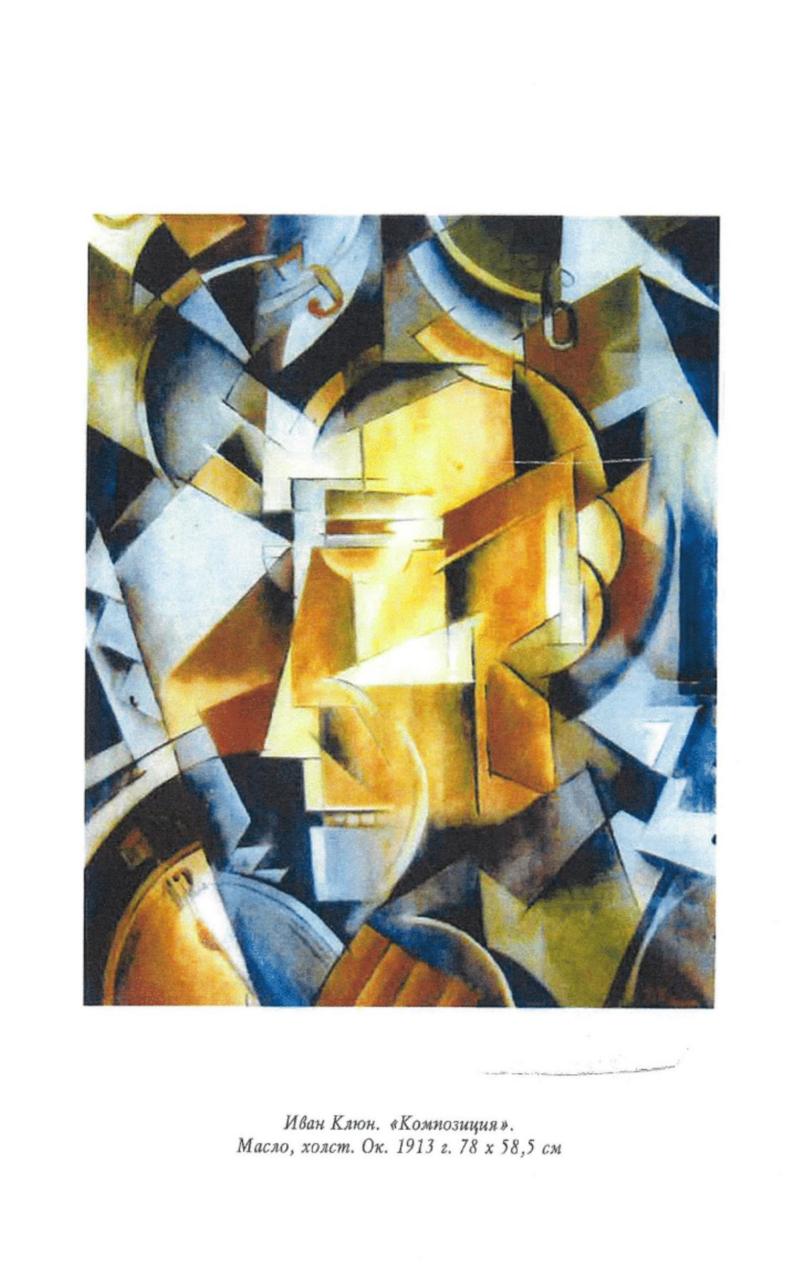

Две работы из коллекции Закса находятся в Институте искусств Миннеаполиса. Автором первой заявлялась украинская художница Александра Экстер, автором второй — “Часовщика” — Иван Клюн.

Именно “Часовщик” попал в два фильма 2023 года — “Оппенгеймера” Кристофера Нолана и “Чудесную историю Генри Шугара” Уэса Андерсона.

Би-би-си связалась с Институтом искусств Миннеаполиса и сообщила о проверке провенанса коллекции Закса. В музее пообещали провести собственное расследование.

Вскоре после нашего письма картина была снята с экспозиции, и подпись к ней на сайте института поменялась. Теперь она указана как “приписываемая Ивану Клюну”.

Еще одно полотно из коллекции Закса, приписываемое украинской авангардистке Александре Экстер, хранится в художественном музее Кливленда. Кураторы музея заинтересовались результатами расследования Би-би-си, но от комментариев отказались.

Мы обнаружили, что еще одна работа из коллекции Закса находится во всемирно известной галерее Альбертина в Вене. Она называлась “Генуя” и также приписывалась авангардистке Экстер.

В разговоре с Би-би-си представители музея сказали, что проводили собственные проверки картины и что она не экспонируется.

Плоский телевизор в интерьере XVIII века

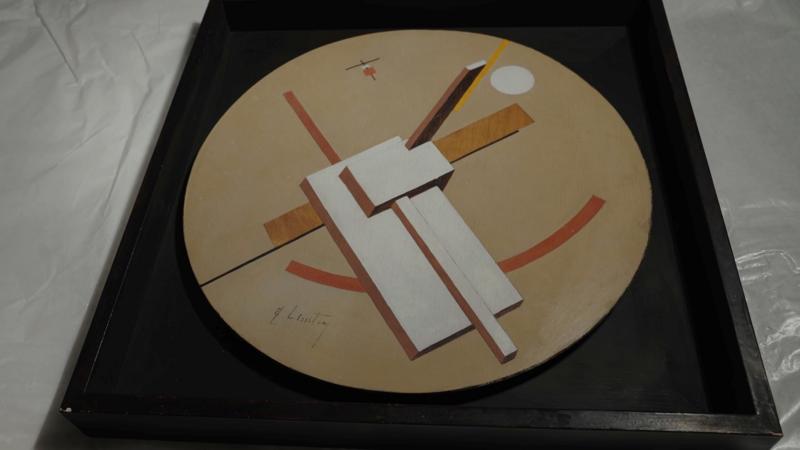

Беатрис отдала Би-би-си две оставшиеся у нее в собственности картины из коллекции Закса — “Проун” (Проект утверждения нового — общее название для всей серии работ) Эля Лисицкого и “Живописную архитектонику” Любови Поповой.

Мы привезли их из Цюриха в лабораторию Art Discovery в Лондоне, где их взялась для нас проанализировать Джиллин Надольны, ведущий ученый в области технико-технологического анализа живописи, развенчавшая десятки подделок русского авангарда.

Ее анализ выявил в картине Лисицкого, умершего в 1941 году, застывшие глубоко в краске волокна, обработанные веществами, которые стали массово доступны лишь после Второй мировой войны.

“Это как картина из 18-го века, у которой на заднем плане виден телевизор с плоским экраном. Это невозможно. Такого не может быть. Так не бывает”.

Картина является подделкой, написала Надольны в своем заключении. Она пришла к тому же заключению насчет приписываемой Поповой картины — “подделка”.

“Всё со слов”

Пока эксперты изучали провенанс и исследовали картины, мы разыскали тех, кто помогал Заксу создать репутацию для коллекции и писал статьи, которые галерея Орландо выдала родителям Беатрис, чтобы убедить их в подлинности продававшихся картин.

Ведущий научный сотрудник Русского музея Антон Успенский — единственный ныне живущий искусствовед, связанный с известным музеем, который положительно отзывался о коллекции Закса. Он опубликовал три статьи о коллекции, в том числе в престижных журналах — “Диалоге искусств”, издаваемом Московским музеем современного искусства, и Academia, издании петербургской Академии Художеств.

Статьи Успенского строятся вокруг якобы проводившихся семинаров против формализма (тех самых, с которых в комиссионки отправились картины, купленные дядей Моисеем в 1950-е). Но в разговоре с Би-би-си он сказал, что сам эту информацию не проверял и все писал со слов Закса: “Это семейные воспоминания, которые никак не подтверждены, нигде не зафиксированы”.

В одной из его статей говорится, что “историко-художественная ценность работ подтверждается экспертными заключениями специалистов международного уровня”. Иллюстрированы тексты фотографиями картин, которые все подписаны как подлинные работы Родченко, Лисицкого и т.д. без знака вопроса.

Тем не менее искусствовед говорит, что не подтверждал подлинность картин, даже никогда не видел ни одной работы, только фотографии, и не знал об использовании своего имени при продаже.

В статьях Успенский также утверждал, что еще один “Проун” Лисицкого из собрания Закса был куплен Базельским художественным музеем. Это не так. “В результате интенсивных исследований наших архивов мы не обнаружили никаких следов семьи Закс вообще или относящихся к ним работ в частности”, — сообщила Би-би-си глава отдела исследований провенанса Базельского музея, который владеет тремя “Проунами”, все — из других коллекций.

Витебский искусствовед Татьяна Котович тоже много и хвалебно писала о коллекции Закса. “Для меня это новость. То, о чем вы говорите, об использовании моего имени. Там же нигде нет заявления, что я гарантирую, что это — этот художник”, — сказала она на вопрос Би-би-си о роли ее статей при продаже картин.

Котович писала, что “Закс плодотворно сотрудничает с виднейшими экспертами”, и перечисляла членов ассоциации экспертов русского авангарда InCoRM, которые выписали сертификаты на многие работы из коллекции, продававшиеся в галерее Орландо.

Вскоре после этого InCoRM попала в центр двух скандалов, когда сертификаты ее членов всплыли на громких судебных процессах о подделках русского авангарда в Германии и Бельгии.

Патрисия Рейлинг, основательница и президент InCoRM, сказала Би-би-си, что организация распалась из-за нападок критиков: “Со всеми этими обвинениями в подделках и клеветой никто не захотел больше связываться…”.

Ошибочные факты

Всё это время мы также пытались поговорить с самим Леонидом Заксом. Мы писали и звонили ему по всем возможным адресам и номерам. Его дочь переслала ему наш запрос, но и тогда Закс не ответил.

И только за две недели до выхода нашего расследования он вышел на связь — и внезапно согласился на телефонное интервью.

Что происходит с той частью его коллекции, которую он не успел продать, и где она сейчас? Закс был уклончив: “Я хотел бы этого вопроса и еще некоторых, других… ценовых и прочих… избегать. Она хранится, эта коллекция, на европейском складе”.

Он отказался от всякой ответственности за проданные на европейском рынке картины:

“Я от этих картин был оторван с того момента, как они ушли из галереи Орландо. Я думаю, что эти вопросы надо не мне адресовать!”

Раз за разом он повторял: “Я ничего не продавал”.

Тогда я попросил рассказать его про провенанс коллекции. Как он может подтвердить рассказы о крестьянах, раздававших модернистские шедевры в 1944—1945 годах?

“А какие доказательства? Вы представляете, что там было после войны?” — нашелся Закс.

Он не стал спорить с тем, что никаких семинаров по формализму в московском клубе МВД не проводилось, и лишь сослался на слова одного покойного искусствоведа, который якобы ему о них рассказал.

В ответ на выводы экспертов коллекционер сказал, что историю коллекции записала его мама, “честнейший человек”, и добавил: “Ну кому я должен верить — неизвестным мне людям или своей собственной маме?”.

Закс говорит, что ему не за что извиняться, и он сам ничего не продавал

Я заметил, что рассказ матери не меняет характер его истории — это семейное предание.

Закс ответил: “То, что написано, это уже не предание, это факт. Может быть, этот факт ошибочный, но это далеко не легенда и не предание”.

Больше, чем мои вопросы о подделках и выдуманном провенансе, Закса удивили суммы, которые родители Беатрис заплатили за работы из его коллекции. Он утверждал, что его работы не могли стоить по 400 тыс. швейцарских франков — и называл такие суммы “бредом”.

“Я таких денег от галереи Орландо в глаза никогда не видел”, — говорил он.

Закса также обидело, что Антон Успенский сказал Би-би-си, что не видел картин и не участвовал в их продаже, а не защитил его коллекцию.

“Успенский бывал в галерее Орландо, и не один раз, кстати. И он видел, что это за галерея, как она работает. Он знал, что это коммерческая галерея типа магазина”, — настаивал Закс.

“Волна подделок затопила весь мир”

В самом конце нашего разговора я спросил Закса, не хочет ли он извиниться перед Беатрис.

“Я извиняться не могу, а посочувствовать я могу. Не за что извиняться”, — ответил он.

Обманутые коллекционеры дорогих полотен редко вызывают сочувствие. В конце концов, это богатые люди с лишними деньгами.

Но в случае Малевича, Лисицкого, Экстер, Поповой, Гончаровой и других мастеров авангарда, это уже давно не просто вопрос потерь частных покупатели — а угроза всему их наследию.

“Подделок значительно больше, чем подлинных вещей”, — говорит Андрей Васильев.

История коллекции Закса показывает, как легко сомнительные картины с придуманной историей могут попасть в ведущие мировые музеи. Там их видят сотни тысяч людей, они попадают на страницы учебников, и на них учится новое поколение искусствоведов.

Именно засилье “фальшака” заставило Акиншу, Васильева и Баттервика заниматься борьбой с подделками. Но порой даже они отчаиваются и допускают, что исход этой битвы уже известен.

“С помощью многочисленных историков искусства, мнящих себя академическими учеными и в то же время щедро выписывающих сертификаты в подтверждение подлинности сомнительных произведений, [авангард] превратился в гигантскую комнату кривых зеркал, населенную ужасными близнецами”, — писал Акинша в одной из своих статей.

Со многими потерями творчество радикальных экспериментаторов той эпохи — русских, украинских, еврейских художников — все же смогло пережить гонения советской власти, Вторую мировую войну и железный занавес.

Но десятилетия рыночного бума и вызванная ими волна подделок угрожают похоронить их наследие под горами плохих копий.