Согласятся ли с компромиссом, который предлагает музей, общественность и киевская власть?

35 лет назад Киевсовет принял решение о создании в доме на Андреевском спуске, 13 музея Булгакова, открытие состоялось 15 мая 1991 года. Доживет ли музей в водовороте декоммунизации и деколонизации до следующего юбилея?

«Да, конечно, — уверяет „Главком“ глава Украинского института национальной памяти (УИНП) Антон Дробович, — Самому музею, то есть музейной коллекции, ничего не угрожает. Разве что он изменит название. Тем более, что там работает профессиональный коллектив, который может рассказать правду о Булгакове без спекуляций».

«Положение закона о декоммунизации касается публичного пространства, то есть названий улиц, памятников и названий юридических лиц», — разъясняет Дробович позицию Института памяти относительно недавнего заключения экспертной комиссии, которая признала памятные знаки и памятники Булгакову символами российской имперской политики. Дробович считает, что признание символами враждебной империи не означает автоматический запрет всего, что связано с писателем. А вот памятник Булгакову рядом с усадьбой возле дома №13, скорее всего, будет подлежать демонтажу.

«Мы здесь не ждем „русский мир“, напевая каждый день „Белой акации гроздья душистые“, — эмоционально реагирует историк и ведущий научный сотрудник музея Анна Путова, имея в виду: музейщики работают, переосмысливают, и работа эта — на благо Украины.

В прошлом году начали работать над обновлением экспозиции, в феврале 2024-го ее презентовали посетителям. И это уже история не о Михаиле Булгакове и романтизированной советской интеллигенцией 1970-1990 годов «Белой гвардии». Это история украинцев, киевлян в двух связанных войнах — начала ХХ в. и нынешней, начала ХХІ-го.

Что же изменилось в музее? «Главком» побывал на экскурсии.

Два мира, две войны

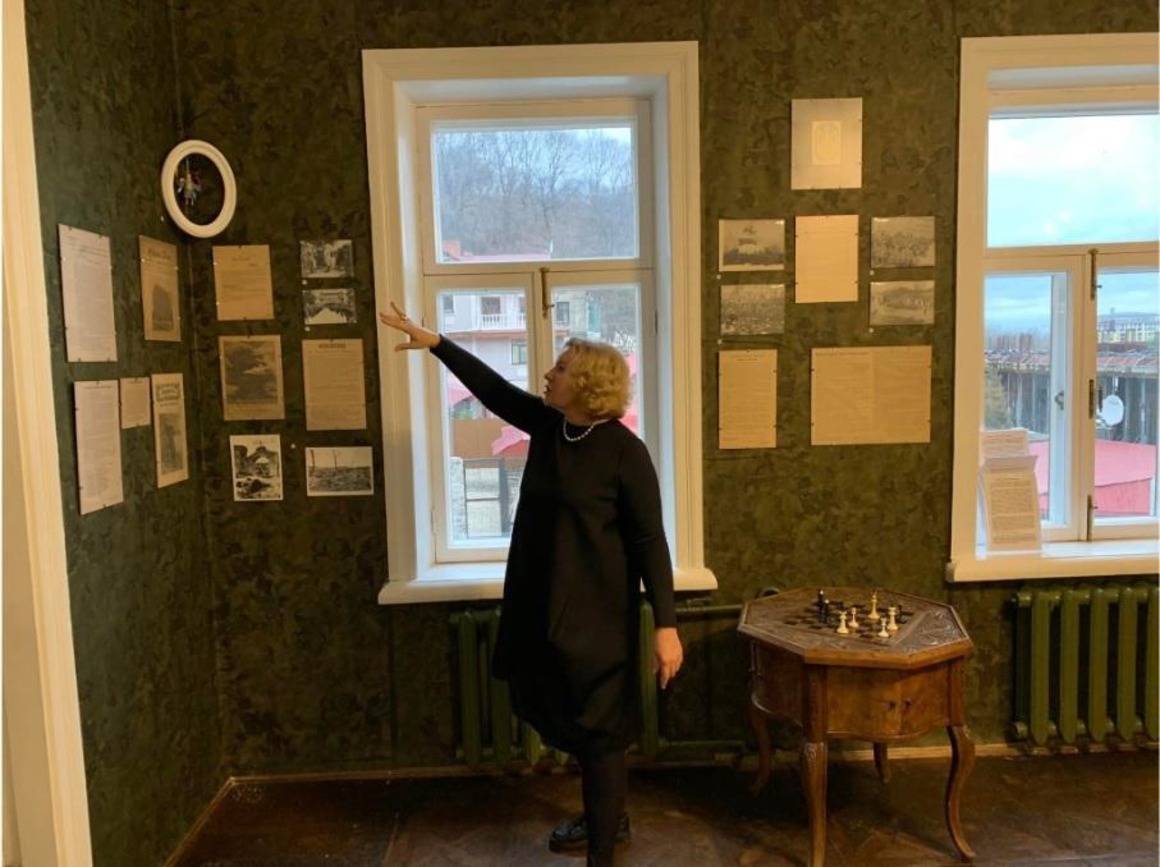

Анна Путова ведет «Главком» на второй этаж, где жили Булгаковы и где недавно открылась новая выставка, названная цитатой из эссе писателя «Киев-город»: «…И внезапно, и грозно наступила история».

Год назад мы писали о том, что ожидается новая концепция, над которой работал музей. Сейчас музей работает в режиме выставок, занимается мониторингом общественного запроса, пока не будет окончательно определено, какой будет новая постоянная экспозиция.

«Когда мы поднимаемся по лестнице, то на стенах видим образы тех, кто принимал участие в первых освободительных соревнованиях: здесь и немцы, и воины армии УНР, и гетман Скоропадский. Виртуально врываются в квартиру красные — и разрушают привычный мир. Цветы вырастают из крови их жертв и льются в прихожую квартиры», — объясняет образы Путова.

«Старая» экспозиция включала аутентичные предметы интерьера, в частности, принадлежавшие Булгаковым (они были своего первоначального цвета) и специально созданную мебель белого цвета, которая символизировала одновременно идею чистого листа, зимнего Киева, а также белых цветущих весенних садов. Нынешнее оформление также состоит из двух частей, только разделяет их не цвет. В игру вступает особая организация пространства, когда половина комнаты является миром дома и домашнего уюта, а другая половина — миром улицы, где нет кремовых штор, потому что они уничтожены, и спрятаться за ними герою не удастся.

Часть, символизирующая улицу, обита спанбондом, в музее из него плетут маскировочные сетки для фронта. Спанбонд изготавливают на основе фотографий зелени, в данном случае были использованы снимки знаменитых киевских каштанов. Таким образом война украинцев за независимость 1918 года переплетается с нынешней.

На стенах комнат — документы и фотографии. Большую часть предоставили коллекционеры и историки: Олег Войтович, Михаил Кальницкий, наследники исследователя Киева Виктора Киркевича.

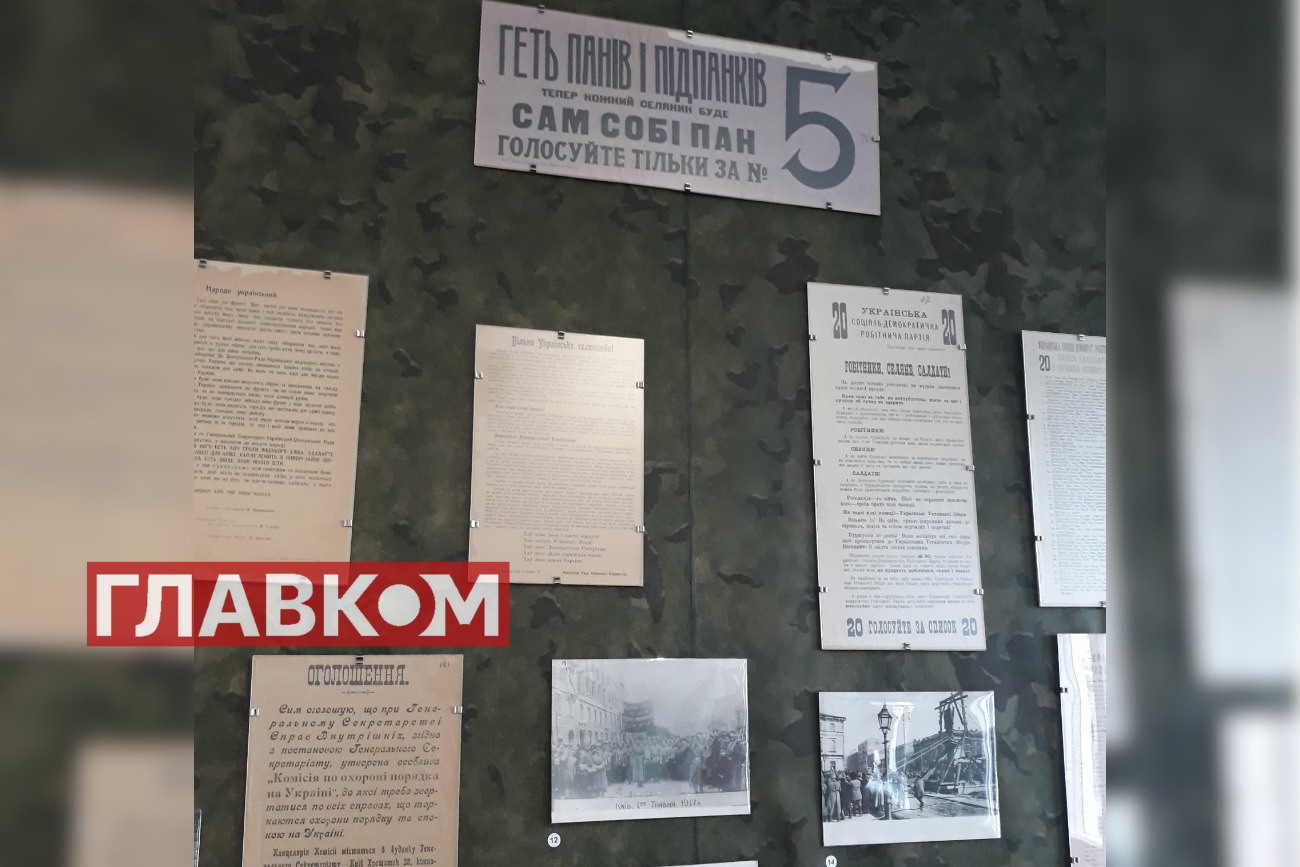

«Вот здесь лозунги, связанные с выборами в Учредительное собрание 1917 года, которые так и не провела Центральная Рада. Далее 1918 год — наступление на Киев Красной армии под командованием Михаила Муравьева. Дикие орды, которые двигались с востока, уничтожили в Киеве пять тысяч человек, и это только за три недели своего пребывания. А вот экспонат, переданный Кальницким: газета «Наши дни» размещает фото дома, в котором находились мастерская художника Василия Кричевского и квартира Михаила Грушевского. Этот дом был уничтожен прицельным артиллерийским огнем большевиков, чем Муравьев очень гордился», — рассказывает Анна Путова.

Комната сестер Булгакова также разделена на внешний и внутренний мир. Внешний описывает жизнь женщин того времени.

«Сестры были сторонницами женской эмансипации, очень самостоятельными. Мама пишет дочерям Надежде и Вере: «Вы обе находитесь в исключительно благоприятных для работы условиях. Я даже представить не могу, чтобы вы были так слепы, что не замечаете, что делается вокруг вас… и как хорошо надо вооружиться знанием, подготовиться к работе, чтобы выйти на арену жизни, если не хочешь вести жалкое существование где-то в хвосте, в обозе бессильных и неумелых»… Эти слова перекликаются с общими установками того времени. Здесь — портреты трех женщин, которые олицетворяют мейнстрим того времени: София Русова, Надежда Суровцева и Людмила Старицкая-Черняховская», — рассказывает Путова.

Педагог и писательница Русова известна прежде всего тем, что создала первый украинский детский сад в Киеве и преподавала во Фребелевском институте, где училась Вера Булгакова. Суровцева, общественный деятель, министр иностранных дел УНР, была первой украинкой, которая имела степень доктора философии, впоследствии подверглась репрессиям за свою деятельность. Отбыв срок в советских лагерях, она осталась в коммунистической Украине, жила в Умани и вела памятникоохранную деятельность. Дочь Старицкой-Черняховской, Веронику, расстреляли большевики, а сама писательница и общественный деятель умерла в вагоне для скота по дороге в ссылку.

Все эти женщины занимали должности в украинских правительствах.

«В УНР женщины имели право и избирать, и быть избранными, в отличие от европейских государств тех времен», — отмечает экскурсовод.

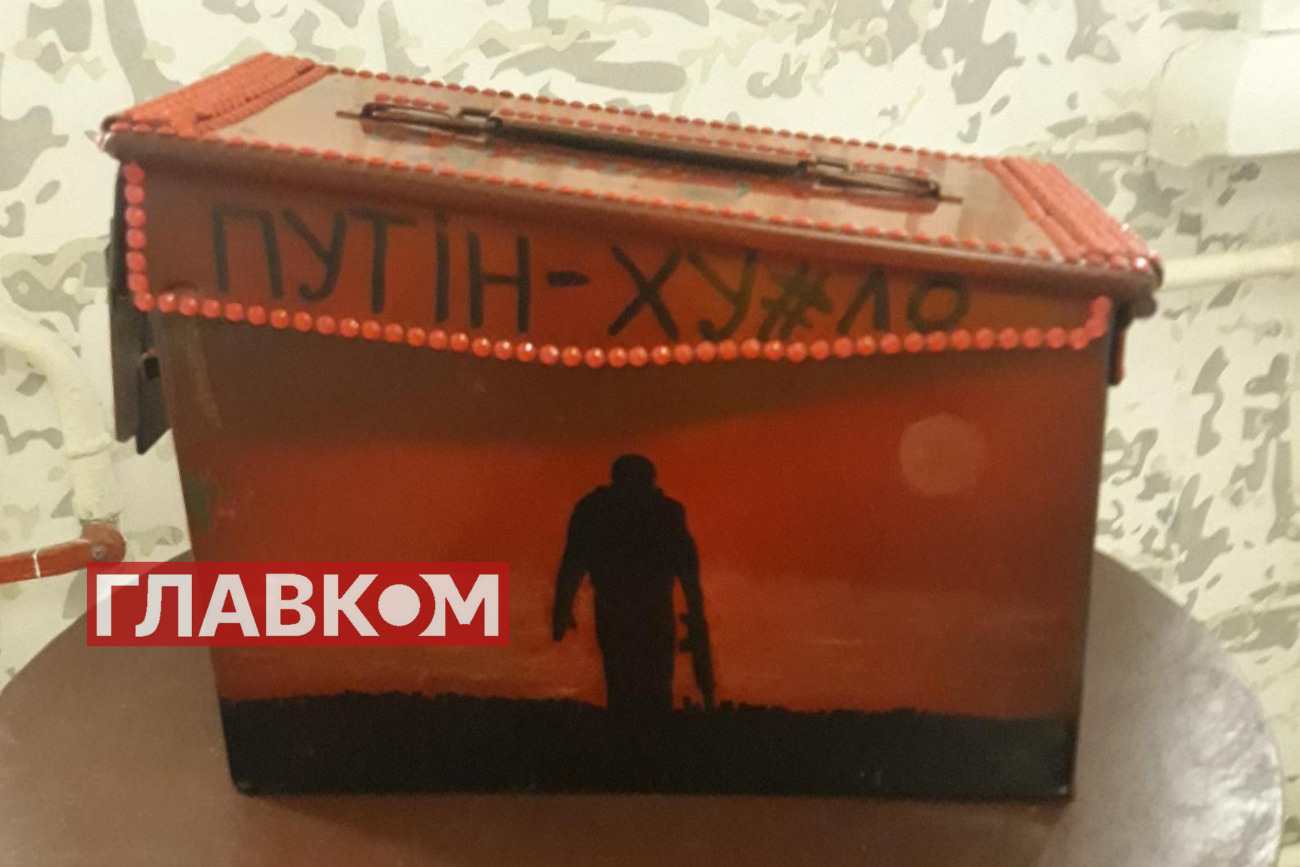

Переход из «женского» мира в «мужской» происходит через шкаф, на дверях которого табличка «50» является аллюзией на «нехорошую» квартиру из романа «Мастер и Маргарита». В шкафу — куртка современного украинского военного, который воюет в Донецкой области. Военные артефакты в экспозиции — как акцент сегодняшнего дня, погоны и шевроны, нынешние и тогдашние, современные гильзы от патронов и образный чемодан мужчины, который собирается на фронт.

Поэтому переходим в седьмую комнату музея — мир мужского выбора, места, где в последний раз пересекаются женское и маскулинное.

«Стол, накрытый камуфляжной сеткой, на нем форма для творожной паски, которая называется „Голгофа“, и яйцо как символ Воскресения. В украинских эмигрантских пасхальных открытках было поздравление «Воскрес Христос, воскреснет и Украина». Это чрезвычайно важный посыл для нас нынешних», — подчеркивает Анна Путова.

Музейщики подчеркивают: нынешняя выставка посвящена освободительной борьбе 1917-1921 годов. Семья Булгаковых, которая в это время жила в Киеве, естественно, оказалась в водовороте событий. Музей рассказывает историю киевской семьи, неразрывно связанную со всеми политическими перипетиями, свидетелями которых она стала. Контекст времени здесь особенно важен, на нем и сосредоточено внимание рассказчика и экскурсанта.

«Если есть эта новая экспозиция, то я удивлен позицией музея, который продолжает стремиться оставаться музеем Булгакова. Надо ознакомиться со всем самому, чтобы понять, как это все возможно совместить — Булгакова и освободительную борьбу», — рассуждает бывший глава Института национальной памяти, народный депутат Владимир Вятрович, которому „Главком“ кратко пересказывает увиденное и услышанное во время экскурсии.

Что не так с музеем?

Владимиру Вятровичу, как и значительной части украинцев, Булгаков сегодня представляется олицетворением «русского мира». С таким подходом категорически не согласны работники музея, которые адвокатируют писателя.

Взгляды, которые артикулирует Вятрович, созвучны недавнему заключению экспертной комиссии, работавшей по заданию Института национальной памяти и в результате признавшей памятные знаки и памятники писателю символами российской имперской политики.

Когда после экскурсии мы пьем чай на веранде усадьбы дома №13, директор музея Булгакова Людмила Губианури разъясняет позицию музейщиков относительно выводов экспертной комиссии.

Во-первых, говорит она, неизвестна методология, которой руководствовалась экспертная комиссия, которая обнародовала только свой вывод, не разъяснив сам процесс.

Во-вторых, по мнению директора, Институт национальной памяти должен был привлечь музейщиков к обсуждению.

«Но они заранее решили, что являются судьями, а музей Булгакова — коллективным преступником. И в этом есть большая проблема в коммуникации между институтами», — отмечает Губианури.

В-третьих, экспертная комиссия все-таки имеет роль совещательного органа, который доказывает свое мнение Институту, а тот уже дает рекомендации КГГА.

«Дробович попросил комиссию пересмотреть выводы и приобщить наш ответ. Сейчас над этим работают», — информирует Людмила.

В любом случае памятник Булгакову, что рядом с усадьбой, могут убрать, однако музейных фондов деколонизация не касается, считает Антон Дробович.

«Музей не находится под угрозой (ликвидации — „Главком“)», — уверяет чиновник.

Институт национальной памяти действительно обратился к комиссии экспертов с просьбой уточнить сделанные ею выводы и принять к сведению позицию музея. На вопрос «Главкома» о том, когда будут подготовлены эти уточнения, Дробович отвечает, что у комиссии, состоящей из девяти известных историков, докторов наук из разных университетов страны, много работы, и связана она не только с Булгаковым.

«Со временем, когда у комиссии дойдут руки, она обнародует и новые выводы, и методологию своего исследования, на чем так настаивает музей», — уверяет руководитель Института.

Можно ли «перепрофилировать» музей Булгакова?

Дробович, впрочем, предполагает, что музею придется изменить название.

С этой идеей не соглашается Людмила Губианури: «Я только не понимаю, мы что, будем в подполье? То есть вывеска появится другая, а внутри мы будем рассказывать о Булгакове?».

Учреждение можно было бы назвать «Музеем семьи Булгаковых» или «Музеем семьи Булгаковых и Глаголевых», предполагает Дробович. (Заметим, что киевская семья Глаголевых-Егоричевых, внесенная в список Праведников народов мира, не имеет отношения к усадьбе на Андреевском спуске, 13).

Хотя члены этой семьи были знакомы с Булгаковыми, а священник Александр Глаголев венчал Михаила с его первой женой Татьяной Лаппой и стал прототипом одного из героев романа «Белая гвардия», и музей имеет коллекцию семьи Глаголевых, переданную потомками отца Александра.

К адресу Андреевский спуск, 13 ошибочно привязывают еще одну фигуру — композитора Александра Кошица. Сейчас на музее Булгакова установлена доска, на которой указано, что Кошиц проживал в этом доме. Но это не соответствует исторической правде.

Доску Кошицу на здании установили в 2021 году два общественных союза — «Музыкальный батальон» и «Народный музей Украины», говорит Анна Путова. Музей истории Киева, филиалом которого является музей Булгакова, просто поставили перед фактом, не поинтересовавшись мнением историков.

Между тем, исследовательницы Ольга Мусияченко и Дарья Кучереженко воссоздали киевские адреса Кошица, оперируя различными источниками, в частности, и воспоминаниями самого композитора.

Тот поселился на Андреевском спуске в усадьбе, состоявшей из трех домов — №22, 22-А и 22-Б. По воспоминаниям владельца усадьбы Ивана Шатрова, он купил ее у мещанина Серкова — реального прототипа комедии Старицкого «За двумя зайцами». Кстати, в воспоминаниях самого Кошица адрес Андреевский спуск, 13 не упомянут ни словом.

Владимир Вятрович предлагает сделать акцент обновленного музея на владельце дома, где Булгаковы арендовали второй этаж. Речь о Василии Листовничем.

Василий Павлович Листовничий не обделен вниманием музея — первый этаж здания хранит память о нем.

«Вот уголок, посвященный Листовщику. Здесь на фото его мастерская. Вот картина, написанная его дочерью Инной. Ноты, переписанные рукой его жены Ядвиги Викторовны. Этот дом Василий Листовничий купил в 1909 году, когда в нем уже три года жили Булгаковы, и оставил себе первый этаж — по просьбе Варвары Михайловны, матери Михаила Булгакова», — рассказывает Анна Путова. По ее словам, о личности Листовничего широкая общественность узнала благодаря выставкам и публикациям музея Булгакова, который много лет разрабатывал эту тему.

В 2021 году, к 80-й годовщине трагедии Бабьего Яра, музей проводил выставку «Дом, который спасает», которая рассказывала о двух связанных с Булгаковыми семьях спасателей евреев. Первая — уже упоминавшиеся Глаголевы-Егоричевы. Вторая — семья Листовничих-Кончаковских, владельцев дома. Их отметили почетным званием, установленным Еврейским советом Украины: праведники Бабьего Яра

Мнения и эмоции общественности, ученых радикально разбежались, и это, несомненно, сказывается на нерешительности властных институтов в определении дальнейшей судьбы музея Булгакова. Но музейщики надеются, что в этом вопросе правду истории не подменит ни конъюнктура сегодняшнего дня, ни конъюнктура дня вчерашнего.